I read Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence years ago and listened to an audio version of it after I completed my A Studio on Bleecker Street. I mention this because in my recent revisit to the novel set in 1870s Gilded Age New York, I realized how many elements of Studio related to elements in Age. Indeed, my characters occupy space that Wharton’s characters occupy at just about the same time.

My Bowman family lives not far from the Archers and Wellands but in one way–and I say this pretentiously–my heroine Clara Bowman does what Wharton’s hero Newland Archer does not do. This makes my story…different and [spoiler alert] not as sad.

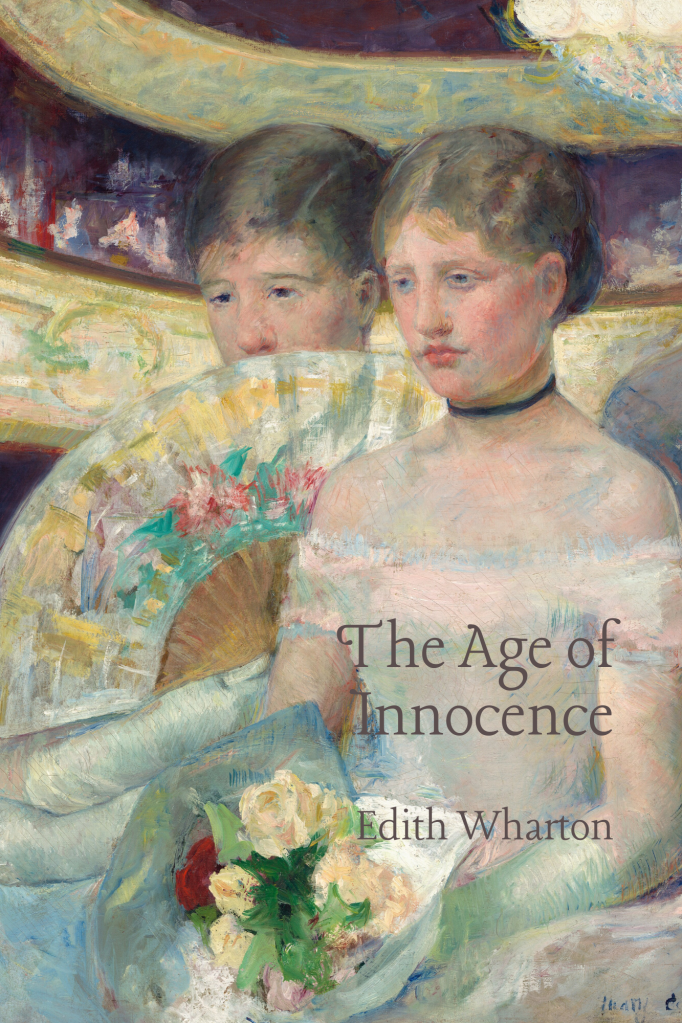

That said, The Age of Innocence begins at the New York Academy of Music. Within not many years–and the novel was published in 1920 but set in the 1870s (except for the final scenes)–the Academy would be eclipsed as the venue-of-the-upper-class by the Metropolitan Opera. The opening scene at the Academy is quite alive, combining the novel’s three main characters, most ominously Countess Ellen Olenska.

The cover for this was clear. The American Mary Cassatt did a number of Impressionist paintings at the Paris Opera. So to the Paris Opera it was, and the cover is from 1878-1880, only a year or two after the events of Age of Innocence. A side note: my heroine, Clara, spent time in Paris studying the artists there; turning to art was her means of overcoming the tragic loss of her best friend and of that friend’s brother, who all knew Clara would marry. (Excerpt.)

The painting is one of several set there, but this one, at the National Gallery, is published free of all rights, i.e., a CC0 designation. The National Gallery describes it:

Shown from the knees up, two young women with pale, peachy skin wearing white gowns sit close together and almost fill this vertical painting. The women are angled to our left and look in that direction. The young woman on our right has a heart-shaped face, dark blond hair gathered at the back of her head, and light blue eyes. Her full, coral-pink lips are closed, the corners in greenish shadows. Her dress is off the shoulders, has a tightly fitted bodice, and the skirt pools around her lap. The fabric is painted in strokes of pale shell pink, faint blue, and light mint green but our eye reads it as a white dress. She wears a navy-blue ribbon as a choker and long, frosty-green gloves come nearly to her elbows. She holds a bouquet in her lap, made up of cream-white, butter-yellow, and pale pink flowers with grass-green leaves and one blood-red rose. Her companion sits just beyond her on our left and covers the lower part of her face with an open fan. The fan is painted in silvery white decorated with swipes of daffodil yellow, teal green, and coral red. She has violet-colored eyes, a short nose, and her dark blond hair is smoothed over the top of her head and pulled back. She also wears long gloves with her arms crossed on the lap of her ice-blue gown. Along the right edge of the painting, a sliver of a form mirroring the torso, shoulder, and back of the head of the young woman to our right appears just beyond her shoulder, painted in tones of cool blues. Two curving bands in golden yellow and spring green swiped with darker shades of green and gold arc behind the girls and fill the background. The space between the curves is filled with strokes of plum purple, dark red, and pink. The artist signed the lower right, “Mary Cassatt.”